Scientists solve the curious case of Himalayan glaciers resisting global warming

3 min read

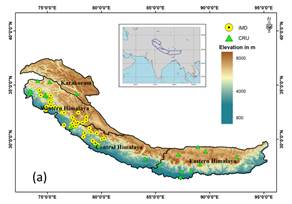

Researchers have taken a significant leap toward solving the mystery of why few pockets of glaciers in the Karakoram Range are resisting glacial melt due to global warming, defying the trend of glaciers losing mass across the globe, with the Himalayas being no exception. They have attributed this phenomenon called ‘Karakoram Anomaly’ to recent revival of western disturbances (WDs).

Himalayan glaciers are of paramount importance in the Indian context, especially for the millions of dwellers living downstream who rely on these perennial rivers for their day-to-day water needs. They are fast receding under the impacts of global warming, and stifling stress on the water resources is inevitable in the coming decades. In contrast, the glaciers of central Karakoram have surprisingly remained unchanged or slightly increased in the last few decades. This phenomenon has been puzzling glaciologists and providing climate deniers with a very rare straw to clutch at.

Dr. Pankaj Kumar, Associate Professor at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) Bhopal, found this peculiar because the behaviour seems to be confined to a very small region, with only Kunlun ranges being another example of showing similar trends in the whole of Himalaya.

A recent study conducted under his supervision has postulated a new theory to explain this defiance of the impacts of global warming in certain pockets as opposed to other glaciers of the region.

In a paper published in the American Meteorological Society’s Journal of Climate, his group claimed that the recent revival of western disturbance has been instrumental in triggering and sustaining the Karakoram Anomaly since the advent of the 21st century. The study was supported by the Climate Change Programme of the Department of Science and Technology.

It is for the first time that a study brought forth the importance that enhanced WD-precipitation input during the accumulation period plays in modulating regional climatic anomaly.

Aaquib Javed, a Ph.D. student of Dr. Kumar and lead author of the study, said, “WDs are the primary feeder of snowfall for the region during winters. Our study suggests they constitute about around 65% of the total seasonal snowfall volume and about 53% of the total seasonal precipitation, easily making them the most important source of moisture. The precipitation intensity of WDs impacting Karakoram has increased by around 10% in last two decades, which only enhances their role in sustaining the regional anomaly.”

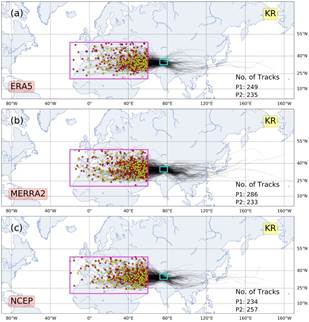

The group applied a tracking algorithm (developed at the University of Reading) to three separate global reanalysis datasets to track and compile a comprehensive catalog of WDs impinging the Karakoram-Himalayan region in the last four decades. The analysis for the tracks passing through the Karakoram reveals the role of snowfall as a crucial factor in mass balance estimations.

While previous studies have highlighted the role of temperature in establishing and sustaining the anomaly over the years, it is for the first time that the impact of precipitation in feeding the anomaly has been highlighted. The researchers have also quantified the impact of precipitation in feeding the anomaly.

Calculations by the scientists reveal that contribution of WDs in terms of snowfall volume over the core glacier regions of Karakoram have increased by about 27% in recent decades, while precipitation received from non-WD sources have significantly decreased by around 17%, further strengthening their claims.

“The anomaly provides a very bleak but nonetheless a ray of hope towards delaying the inevitable. After recognising the importance of WDs in controlling the anomaly, their future behaviour might very well decide the fate of Himalayan glaciers as well,” Dr. Kumar pointed out.

Publication link: https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0129.1